Punk Rock Entrepreneur: Running a Business Without Losing Your Values

Want to make a living without selling your soul?

Do you have an idea for something that you want to share with the world but don’t know where to start? Want to make a living without selling your soul? Have a business plan but can’t afford to buy anything up front? This book is for you.

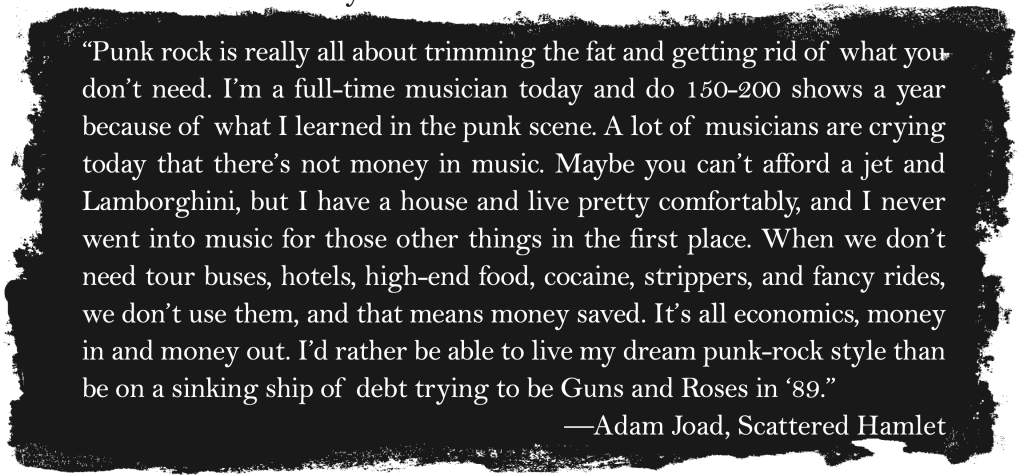

Punk Rock Entrepreneur is a guide to launching your own business using DIY methods that allow you to begin from wherever you are, right now. Caroline Moore talks (and illustrates!) you through the why and how of business operations that she learned over years booking bands, organizing fests, sleeping on couches, and making a little go a long way. Engaging stories and illustrations show you the ropes, from building a network and working distribution channels to the value of community and being authentic. The second edition features a new introduction by Lookout! Records co-founder Larry Livermore.

With first hand accounts from touring bands and small business owners, this book gives you the inspiration and down-to-earth advice you’ll need to get started working for yourself.

Read on for an excerpt of Punk Rock Entrepreneur: Running a Business Without Losing Your Values by Caroline Moore, available for preorder from our site (shipping starts 5/31/25) or your local bookseller (officially hitting shelves 8/26/25)!

I can’t remember the exact moment I decided to start a business. I have always done work on my own, outside my regular employment. Before I even graduated from college with my design degree, I had started picking up freelance work that I could use to pump up my portfolio for when I later applied to agencies. Despite a solid resume and a shiny new MFA, I couldn’t overcome a saturated job market. Friends already working in the field reported receiving some 200 resumes for one job posting. There were simply far more designers than there were jobs, and I ended up working whatever day job I was offered. I cut out felt letters for hockey jerseys at a factory, provided tech support over the phone, and worked as a veterinary technician.

All the while, I sought out design clients—less to impress hypothetical agency types and more to do the work I really loved. It was work that I felt compelled to do even at the expense of sleep and social outings. Later, I started offering photography as a service, primarily wedding and portrait work, and eventually I realized that I needed a space online to show people what I did. I set up a basic website to display my photography and design work, and detail my services. It’s been growing steadily ever since. At the time, I didn’t think of it as a business, though I was making money and logging as many hours as I did at my day job. It was just a sort of side- hustle thing that I was doing—something that I wanted to do, was skilled at, and had enough equipment to get started.

So I started. I grew up around people who were always working on projects. If a friend wanted to produce a zine, she would draw one up and distribute it. If she didn’t have all the skills herself, she would collaborate with other kids—authors, artists, publishers—to get it made. Other friends wanted to go on tour, so they’d call venues, hook up with other bands, and ask their dads if they could borrow the old van. When I would ask my friends what made them do these things, they’d just shrug. Because I wanted to or because I can or because I can’t imagine any other way of living. They couldn’t picture a world in which they didn’t approach life that way.

I grew up in a coal patch in southwestern Pennsylvania, which is not generally considered a hotbed of innovation and creativity. Still, I spent most of my time in high school and college around people who made things—music, venues, zines, art. If my friends had an idea, something that they wanted to put out into the world, they figured out the next steps to make it happen, and then they did it. I met people who believed in doing it yourself, in carving your own path, and in questioning established rules and systems. It’s easy to hit an obstacle in your plan and stop there, to declare things to be impossible or, at the very least, just not doable at the moment. But punk kids, and successful entrepreneurs, don’t jump straight to no. Instead of making excuses, they ask, what do we have to do to get this done?

The most important business lesson I learned from the DIY punk scene is that mindset. Punk kids have an attitude about, and a certain perspective on, the way the world works. I learned how to get things done, and quickly. I learned how to connect to people and how to be creative in a lot of ways—not only in the things I make but in getting my work out there. I learned that it’s generally better to ask for forgiveness than permission, that is, if anyone even notices your bold move. These are the things I hope to impart.

You are going to run into obstacles. Whatever sort of business you’re trying to create, whatever work it is that you want to do, will not be smooth sailing. How you handle those obstacles can make or break you. There are plenty of grim statistics about how many businesses fail in their first years and how few make it past five years. Failures generally boil down to a lack of planning (not enough people want what you’re making, you’ve drastically underestimated your operating costs) or an inability to handle hardships when they arise. This attitude that I’ve picked up, thanks to hanging around DIY types, has fundamentally affected how I handle problems. Now, when something goes terribly wrong, my immediate reaction isn’t oh shit, we’re boned but what can we do about this?

Touring is an essential part of getting a band off the ground, so bands have gone to great lengths to make a tour happen. Not having a van is a pretty giant obstacle, but, again, people got creative and found workarounds. DOA opted to hitchhike from Canada to San Francisco and borrowed equipment for their first gig. DRI traded their PA for a van and sold everything that wasn’t nailed down to cover gas money. Operation Ivy toured in a 1969 Chrysler Newport—a four-door car—for six weeks. Pat Spurgeon of Rogue Wave went on tour while waiting for a kidney transplant and had to do dialysis twice a day. Usually, this is done under extremely sterile conditions, but Pat had things to do. So, in the best-case scenarios, he’d get a motel room to himself. In the worst, he did his dialysis in a moving van. The band would roll up the windows, turn off the A/C, and put on surgical masks. It would have been easy for any of those bands to say we can’t do a tour. But they didn’t. Instead, they figured out a workaround to get where they wanted to go.

Some of these plans were better than others. The takeaway here isn’t simply to jump without a net and hope for the best (nor is it to do dialysis in a moving van). It is, instead, to ask what do I need and how do I get it? If that’s not a culture you’ve been immersed in, it can take some effort to change your thought process.

In addition to spending so much time around DIY types, I was also raised by people who made things happen. (My mother once applied for a job while barefoot, on a dare. They hired her.) Yet, I’ve still heard myself say oh, I can’t do that without thinking it through. When I was accepted to give a conference talk in London, my kneejerk reaction was oh, but I can’t fly to London. After a bit of time had passed, I thought, why can’t I fly to London? I have a passport, I’m not banned from that particular country, and I’m great at budgeting and planning trips. Sometimes it takes a conscious effort to follow up that immediate negative reaction with what do I need to make this work and how do I get it? I did the research on what exactly it would cost, planned a way to pay for it, and organized my travel. I made a workable plan.

Get all the facts before you decide that you can’t do something. I can’t is an excellent excuse not to do scary things. It’s vague, so you can’t really argue with it. It sounds as though you’ve thought the situation through. I can’t is just the first roadblock your brain throws out there when faced with a scary task. (It’s right up there with this is the way we’ve always done it.) Usually, my counterargument is what’s the worst that could happen? This is generally a rhetorical question, but considering what is the worst thing that could happen can help you to figure out exactly what is at stake. I can’t lose this job is an immovable roadblock, but I’m worried about how losing this job will affect my budget is a concrete problem that you can begin to solve. Alternately, you may realize that something is an extremely bad idea that you should run in the opposite direction of (i.e. the worst thing that could happen is I fail at this stunt that I’m in no way prepared to perform and end up in a full-body cast). The idea is not to jump straight to no but to carefully consider where saying yes might take you.

Want to keep reading? Check out Punk Rock Entrepreneur: Running a Business Without Losing Your Values by Caroline Moore with a foreword by Lookout! co-founder Larry Livermore, available for preorder from our site or through an independent bookstore near you.